If you were to ask me about which two industries I am certain will continue to exist for the rest of the century, I’m quite sure about my answer. They may not be the most exciting, but the paint (link) and waste industries have and will continue to play a fundamental role in our societies. Both are expected to continue growing roughly in line with GDP. More specifically, in the case of the waste industry (which is what I will focus on today), the World Bank estimates that global waste production will increase by 70% by 2050.

Let's be honest, it's not good news at all, but someone has to manage it – and, therefore, benefit from it. Waste Connections (WCN) is the third largest solid waste services company in North America. It provides non-hazardous waste collection, transfer and disposal services and resource recovery primarily through recycling and renewable fuels generation in 43 US states and 6 Canadian provinces. The company was founded in 1997, but the roots of the modern waste industry in North America go back much further. Judging by current valuations, they are regarded as “defensive” investments by the market (Waste Management, Republic Services and Waste Connections trade at 20, 21 and 27 times EBIT respectively), but this has not always been the case.

The modern waste industry started off with the IPO of Waste Management (WM) in 1971. Their strategy from the beginning was to consolidate a fragmented market with no clear national leader at that time. With the capital raised from its IPO, WM acquired up to 75 local waste businesses across the country in just 18 months. Between 1971 and 1979, revenues grew at a compound annual rate of 48% to nearly $400 million. In just 12 years, WM had multiplied its revenue by 80 (in 1968, when it was founded, it was just $5 million). In 1982, it reached 1 billion dollars and by 1985, it exceeded the 2 billion mark. Not surprisingly, when management teams focus on growing just for the sake of it, they usually end up making some capital allocation mistakes. WM was no exception. Some acquisitions were not quite well integrated, they entered new adjacent business lines with poor unit economics and increased their market share in countries with weak regulatory frameworks.

In addition to the challenge of achieving optimal profitability levels, there was another important one. Other waste companies that had witnessed WM’s success replicated the company’s roadmap. There was increasing competition for new deals, and analysts began to question WM's growth story. If the company’s growth rate slowed down abruptly, the stock price would collapse. This, for a serial acquirer using company stock as currency to make acquisitions, becomes a vicious circle difficult to break.

During 1992-1996 WM's management team, unable to keep up with growth, attempted to remedy it and maximize EPS by cooking the books. The company had temporarily managed to avoid recording some operating expenses by inflating the reserves in connection with acquisitions on the balance sheet. The accounting scandal came to light in 1998 and in 2002 the SEC claimed that the management team had inflated profits by more than $1.7 billion. The waste industry had attracted so much negative attention that the big waste companies divested all unprofitable lines of business as well as their international operations to focus solely on North America.

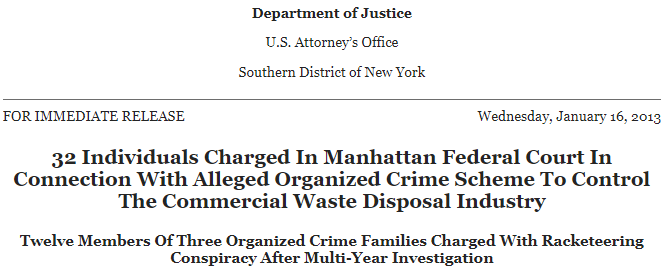

The waste industry was slow to regain investor trust. After all, and while many companies are now enjoying their golden age due ESG tailwinds, this will always be an unglamorous industry. It has changed significantly in the last two decades, but solid waste continues to have a negative value for customers – managing it in a safe and environmentally friendly way costs them money. Environmental regulation has been increasing this cost, and some businesses see it as an encouragement to dispose of their waste illegally to cut down costs. It is not surprising that from time to time courts sanction local companies that fail to comply with the rules or even expose the links of one of them with organized crime.

“By asserting and enforcing purported “property rights” over the trash pick-up routes, the Enterprise members excluded any competitor that might offer lower prices or better service, in effect imposing a criminal tax on businesses and communities.” Source: link